Ah, Koreatown

by Hyun Sook Lee Senteno

A guest has arrived from Peru. My husband and I invited them for dinner, but because it is our first time seeing each other, and we speak different languages, the air between us feels rather awkward. My nephew’s wife acts as a translator between us. Once learning that I am Korean, my nephew‘s sister-in-law Maria, who is sitting across from me, tells me she likes Korean dramas. She takes out her cellphone and shows me a clip of a drama that she is watching. The Spanish subtitles appear on the bottom of the screen. Their ten-year-old daughter Andriana, seeing a Korean for the first time, repeatedly glances over at me. Maria, with an apologetic expression, says she would like to visit Koreatown before she returns to Peru. Ah… Koreatown.

In the early 80s when I first migrated to the United States, I settled down on a Hispanic neighborhood. I was aware that I was in a foreign environment, immersed in foreign language and foreign culture. I would leave the area once a week to go to Koreatown, an hour’s drive away. I looked forward to the excursion, with a fluttering heart, as if I were going to my parent’s home. I felt at home seeing Koreans at Olympic Market—the only store which sold Korean groceries—just because they were of the same ethnic background. I almost wanted to firmly grab anyone’s hands and ask how they were doing as if I had met a close friend from my hometown.

Nowadays, Koreatown has a much wider perimeter and deeper roots. Instead of simply being a residential area for Koreans, it has transformed into a commercial district where Koreans can take care of every need they may have. It is a place where you can make a living without speaking a word of English. I, too, have changed. Perhaps because my lifestyle and ideals have become Americanized in my middle age, the word ‘Koreatown’ no longer strikes a chord in my heart. On top of that, I even take a detour sometimes because I want to avoid the main areas, Olympic Boulevard and Normandie Avenue. This is because of two places that irritate me like a prickly thorn stuck on the tip of a finger.

How VIP Palace, a meeting place for the old timers, has changed pained the very bottom of my stomach. In 1975, the building’s owner had personally transported 10,000 blue tiles and employed dancheong (traditional paintwork on wooden buildings) experts to create an authentic Korean restaurant filled with Korean culture and sentiment. Back then, cooking doenjang (bean paste) stew at my apartment would cause a ruckus among the neighbors because they didn’t know what the smell was. We would often become an annoyance to them due to strong garlic smells. The only place where we could freely eat doenjang stew without worrying about our neighbors was our koreatown. When the restaurant later turned into a buffet, I frequented the place for celebrations such as first-birthday parties and 60th birthday parties.

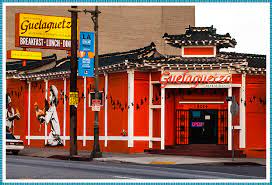

A few years ago, the buffet then turned into a restaurant serving South American cuisine, and I couldn’t believe my eyes. The roof tiles that had once held the savory smell of doenjang, now were buried with the strong fragrance of the South American mole sauce. On weekends, their traditional dance performances take place, and traditional handicraft items are sold at a corner of the restaurant. The walls underneath the blue roof tiles have been painted dark orange with the drawings of the South American children running and playing. The roof tiles and the wall simply do not harmonize. Would there be a way to carefully remove and conserve the blue roof tiles since they will eventually be torn down anyway? What a waste of the colorful dancheong. I feel deep regret since it seems as we Koreans could not protect our own cultural heritage.

Dawooljung, located across the street, makes me even more emotional. The city of Los Angeles donated the property, and the united effort from the overseas Korean community collected the funds to construct the structure. Drawing inspiration from the Octagonal Pavilion in Gyeongbokgung Palace, 16 master artisans from Korea built the structure using the traditional construction method of not using nails or concrete. The Korean style roof tiles were laid and the dancheong was painted. Our people value upholding traditions, and we had much expectations for the structure. We anticipated that it would educate the American mainstream culture about Korea and that it would instill a sense of identity and pride for first and second-generation Korean Americans. I was filled with pride as the pavilion would have been the first Korean traditional work of art located in the United States in over a century of Korean immigrant history. Unfortunately, it’s hard to see Dawooljung lately, hidden by the shadows of large buildings surrounding it. It is stuck inside the steel fences that look out of place next to a pavilion. Trash continues to pile inside the fences. I understand that managing and maintaining the structure like this may be troublesome, but it crouches in the triangular corner where three streets collide like an ostracized piece of garbage. From time to time, politicians who need votes from the Korean-American community proclaim that the area should be ‘newly renovated’ and ‘maintained properly,’ but this is all out of their need and vanishes out of everyone’s minds in a blink of an eye. The true meaning of Dawooljung, a harmonious gathering place, faded away a long time ago. I feel sorry for the koreatown of my heart as it fades away as the passing of time, unable to keep what should be kept. I take a long detour just to avoid the area and seeing what it has become.

Chinatown in the vicinity of Downtown LA begins with the Dragon Gate, formed by two dragons. Between the golden dragons, buildings with red roofs tiles and stores selling traditional items imbued with the Chinese spirit. Chinatown was designed so that upon entering its streets, it instantly feels as if you have stepped into China. Likewise, in Little Tokyo, the torii—a Japanese gate to a shrine that leads to the sacred place—has been built, serving as a gate to Japantown. Traditional restaurants and bookstores are located in low and petite buildings, radiating the Asian style. The Japanese American National Museum has left behind a legacy of Japanese immigration history for their descendents and foreign visitors. The gate and the museum have since become tourist attractions in LA. They draw in foreign visitors, and they tell these foreigners their own narrative.

When I have to entertain foreign guests, I worry from time to time. I would like to show them Korean culture and tradition, but, regretfully, there’s nothing I can show off. Koreatown does not have any buildings or landmarks to tell them about Korea or Korean culture. Foreigners who visit Koreatown to experience Korea may even be disappointed that there are just illegible Korean signs lined up and down the streets. I worry that they might categorize Korea also as a place without any attractions or entertainment.

I feel ashamed before the second-generation Korean Americans. They were born in the United States, and they do not have any tangible symbol to instill the Korean identity or to tell them that their roots are in Korea. Because they are becoming more and more Americanized, they need something to honorably show off as Korean. It is said that history is a dialogue between past and present. History is only meaningful when such dialogue occurs. I have to leave behind a legacy to my children, so they then can pass it down to the next generation.

Instead of making excuses saying that making a living is too difficult, we must carry on our obligation to spread Korean tradition and culture. To suit the name Koreatown, Koreatown must give off the charm of Korean culture. This must be felt so that the visitors will be drawn to this charm.

Since Korean food has become trendy, I will bring the guests to a restaurant in Koreatown and treat them to galbi and japchae. At least in that way, their stomach would be pleased.